Tess Davis who once worked for Heritage Watch in Cambodia and is now executive

director of the Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation in

Washington has written an interesting op-ed piece ('Cambodias

looted treasures', New York Times April 27, 2012) which discusses the trade in portableised art looted from Cambodian temples and other monuments:

Tess Davis who once worked for Heritage Watch in Cambodia and is now executive

director of the Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation in

Washington has written an interesting op-ed piece ('Cambodias

looted treasures', New York Times April 27, 2012) which discusses the trade in portableised art looted from Cambodian temples and other monuments: During the Cambodian civil war from 1970 to 1998, the Khmer Rouge and other paramilitary groups began decimating that country's ancient sites in search of treasures to sell on the international art market. Along with arms dealing and drug smuggling, the looting and trafficking of artifacts became organized industries, which helped finance one of the 20th century's most notorious regimes. My colleagues and I have documented the painful scars from this plunder — desecrated tombs, beheaded statues and ransacked temples — at archaeological sites throughout Cambodia. We've spoken with looters, middlemen and dealers, and have even posed as collectors. The exact path of pillaged objects is admittedly difficult to trace. But when they do surface, more often than not, it is in the legitimate art world.She then discusses the Sotheby's and Norton Simon statues from the temple of Prasat Chen in the ancient capital of Koh Ker in Cambodia ("on opposite coasts of the United States with only their pedestals — and feet — left behind"). In the current state of law, it remains difficult for countries such as Cambodia to "recover their pillaged heritage in legal actions because of a high burden of proof, the statute of limitations and other bars to claims. It's easier to make a moral claim for repatriation". The trouble is of course that we see that such arguments cut little ice with many in the trade of such items.

Actually I think most people buying this stuff do not really care. that is the whole point, it is why they 'ask-no-questions-get-told-no-lies' in the first place.Most of us will never purchase an illicit antiquity from Cambodia or elsewhere, but we are complicit in these crimes. Our inaction allows them to continue. When we see an artifact for sale or on display, we must ask where it came from, and how. The answers should not be hard to provide, as valuable objects usually have a paper trail, from import declarations to insurance forms. But if there is no such provenance — or if it points to the artwork being a victim of war, civil unrest or criminal looting — such a piece should not be on the market or in a museum. When archaeological sites are looted, the history of many is lost for the pleasure of a few. Buying, selling, displaying and even viewing such antiquities means condoning the destruction of art we love, and perhaps even encouraging it. At best, we may be funding criminals; at worst radicals, like the Khmer Rouge (Al Qaeda and the Taliban have also been linked to the illicit art trade). Is that a legacy that Sotheby's, the Norton Simon Museum or anyone would want?

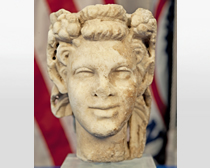

Vignette: Stealing their past (Andy Brouwer)