|

| Roman or Asian folk art? (Photo: PAS who say it's Roman) |

There is some tittering on a Kent newspaper over a recent metal detectorist's find (Sean McPolin, '

Rare Roman penis pendant found by metal detectorist Wendy Thompson' Kent Online, 29 May 2022).

Metal detectorist Wendy Thompson discovered the phallic amulet while searching a farm in Higham, near Gravesend and Strood.

Mrs Thompson, who lives on the High Street in Lydd, found the cast silver item on December 31, 2020 [...]

Coroner Roger Hatch described the item, detailing its "foreskin, shaft and pubes", before reading a short report from the British Museum.

The report said it was hard to narrow down an exact date for the pendant but believes the phallic nature of it "points to the Roman era".

It added: "This is the first silver item of its class and is a significant national find".

The news item did not report that the object was not identified or reported by an FLO, but

the record (PUBLIC-E168F3) was created by a volunteer member of the public with an unknown amount of input from anyone else (PAS records are now published anonymously). There are problems with the phrasing and the account concentrates largely on the metal it is cast from. The purported parallels taken almost entirely from the PAS' own database totally miss the mark (in passing it may be be noted that the use of the term term "flaccid phallus" is found mainly among archaeologists and ornithologists - since a phallus φαλλός is by etymology and definition an erect penis). The anonymous author notes

"This example is different in form to most example recorded on the database however, with the omission of testicles, and the inclusion of pubic hair. [...]

It is not possible to narrowly date this pendant, as not direct parallel with secure dating evidence can be found. The large corpus of phallic imagery across the Roman Empire however, strongly points to a exclusively 'Roman' tradition, and thus, in the case of phallic objects found in Roman Britain, a date of 43-410 AD can be confidently (sic) assigned".

There is another difference the confident, but anonymous author did not note. The vast majority of the phallic amulets from the Roman Empire, so not just Britain, have the suspension loop on the dorsal surface of the phallus, apparently intending to suggest or (where the balance produced by the position of the testes is correct), effect that the penis is suspended projecting horizontally. This one has the suspension loop underneath, where the missing testes should be. Also the Higham pendant has a very thickened distal end, whereas most Roman phallic talismans (both the real ones and the fake ones on eBay) go for length rather than girth, and tend to be more evenly cylindrical.

I really find it incomprehensible that in assessing a loose metal object from the top 25 cm of cultivated land (it says in their own record) a recorder did not ask him or herself the obvious question, where else could this have come from? An anomalous object like this found loose with no context needs always to be considered as a potential modern intrusion, perhaps lost by a collector, a traveller, a local from a minority culture, or even planted deliberately (as a joke or to give paying members something interesting to find on a long-past club dig or rally).

Phallic amulets and talismans are not restricted to Europe or the Romans, and certainly not just the first four centuries AD, and it is bonkers to think that they even could be. There are a whole range of them in other countries, ancient and modern. In particular they are found as the Buddhist Palad Khik amulets in SE Asia (Thailand) in particular. These have a variety of shapes and come in a variety of materials and price ranges, but generally stress girth (boosting the wearer's feeling of male strength). Some of the traditional ones also differ from the Roman ones by many of them having the suspension loop at the proximal end, or sometimes underneath so they hang pointing downwards. There is also a series of necklaces from at least two areas of Africa that have long metal beads, looped at one end projecting

laterally from a necklace string and separated from each other by spacer beads.

While I have not searched for a specific parallel, I consider that to ignore the existence of this body of material (by those who ARE paid to do that research) to be a serious lack of due diligence.

After all, the law is that to be Treasure there has to be more than 10% precious metal there and the object has to be more than 300 years old. It is not stated in the report how the metal was established (was an analysis done? This object was recorded in a state already cleaned down to bare metal, so we cannot see the corrosion. Is it really silver and not some other white metal used for making charms? How can it be said on the evidence presented by the PAS that this dates to before 1721 (when we can still buy such amulets on eBay prior to our date with some local farm lass for a romp in the haystack)? There is no evidence from that

PUBLIC PAS report that either have actually been demonstrated.

Without a context, and without a properly-grounded precise parallel, it could equally be an entirely modern loss of an object knocked up in a Bangkok garage workshop and made of a completely non-precious metal from melted down scrap. It may not be, but until the PAS can provide evidence of better research, and a properly-grounded parallel, that possibility cannot be ruled out, and the law cannot be applied based on mere guesswork - whoever did it.

UPDATE 5th March 2023

On going through the PAS database for something else, I chanced upon this "record" today and note that it was "Updated: 4 months ago". So after my post here. It now says: "

Object type: PENDANT

Broad period: MODERN" but then elsewhere in the same record it still reads: "A complete cast silver phallic amulet or pendant of Roman date (c. 42-410 AD)". Whoah. Consistency and professionalism as always, eh? The record goes on:

Conclusion: It is therefore clear that this object likely dates to before 1721 and, as the object is made of more than 10% precious metals, it constitutes potential Treasure under the stipulations of The Treasure Act 1996 [...]

This object is the first silver example of its class purported to be discovered, and thus a significant national find.

Would be if it was a Romano-British artefact, eh? But an added note is interesting in the context of my above comments:

Notes:

This object was recorded as a PUBLIC record as directed by the FLO while they were on long term sick.

(a) that is not grammatical, and (b) what difference does it make? Surely a database should have data entries of consistent quality independent of who is doing the actual writings (and these entries are not signed). But it gets more interesting, look what they then did:

Addendum:

Non-destructive X-ray fluorescence analysis of the surface of an amulet from Higham, Kent indicated a precious metal content of approximately 77-79% silver and 21-23% copper. No other elements were detected. This composition is not consistent with the amulet being older than 300 years and therefore is not Treasure as defined under the terms of the Act.

The amulet weighs 9.66 grams.

[unsigned] Department of Scientific Research

The British Museum

September 2022

Do you see that? If you'd written your chemistry/physics experiment in the grammar school I went to, you'd have got a pretty devastating remonstration from the teacher (sadly passed away last year). I guess not all of us were so lucky with our teachers.

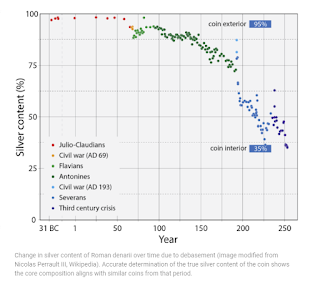

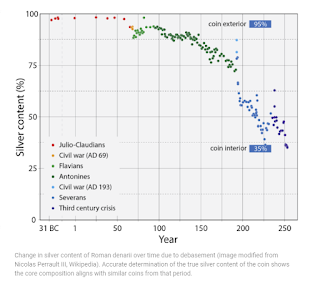

"X-ray fluorescence analysis" done [by whom, and with what aim] in what way? Handheld? Surface treatment, how many points, how many measurements? "No other elements were detected", which ones were sought? "This composition is not consistent with the amulet being older than 300 years" what? So which compositions would be "acceptable", and can the Scientists at the BM not have provided some literature to back up that statement - specifically one that states explicitly that "no silver alloy of a composition 77-79% silver and 21-23% copper could ever be older than 300 years"? I really do not understand how they can say that without making reference to some benchmarks. As it happens, we have quite a lot of analyses of silver denarii. Coineys love to write about the decline in the silver content silver... lots and lots. So we can find some nice tables full of analyses, which show... oh, Roman silver alloys can indeed be "77-79% silver and 21-23% copper" - denarii of c. 150-c. 170 for example (see the figure here taken from

just one accessible work where this can be seen). That is the reigns of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. And yes, when we get analyses of Roman silver vessels, not surprisingly they often have similar composition to the coins... so for example the Sevso hoard analysed has relatively pure silver with only traces of lead and gold (some at least of which may be from they having been made not directly from coins used as bullion, but older metal vessels). One vessel has higher bismuth content alongside the silver and copper. There are not too many analyses of second century hoard vessels from the Western Empire but I think we all deserve to see at least one or two cited here to show that they are TOTALLY DIFFERENT from the alloy this analysis detected.

What is going on here? My text is about a report of a Treasure inquest in May 2022. Presumably the PAS record was written (the PAS are not precise enough to say when, it currently says "

Created: About one year ago") prior to that - it said that the "Roman" "silver" object was potential Treasure [

Treasure case number: 2021T651]. And so it seems it went to Inquest and the Coroner, on the basis of what the PAS had said, pronounced it Treasure. But then who actually wrote that entry, relied on by that official? We are not told, just it is [a member of the]"public". Was it in fact the finder? So the inquest was in May, Barford wrote about it at the end of May, pointing out why that object is highly unlikely to be Roman because it looks nothing like the Roman ones that are pretty single-mindedly variants on a theme. I suggested there are good reasons for thinking it was something else and the PAS was letting everybody down not considering the wider background. Is that why the BM decided to do an analysis after-the-fact and pronounce that the results "prove" the object is "not older than 300 years" - but without in ANY WAY substantiating that

deus ex machina statement. Note that, depending on the precise wording of their agreement, by this move the landowner has been deprived of a potential half a Treasure award for "the first silver example of its class purported to be discovered,

and thus a significant national find ". That is of course if it what the anonymous Public writer of the original PAS entry says it was. Which of course it is not. And why are the PAS not saying that in their revised entry? Where's that outreach they are supposed to be doing? Maybe now the FLO is presumably back from their "sick", we can see a proper entry here.